William P. Brosgé Receives the 2001 Dibblee Medal

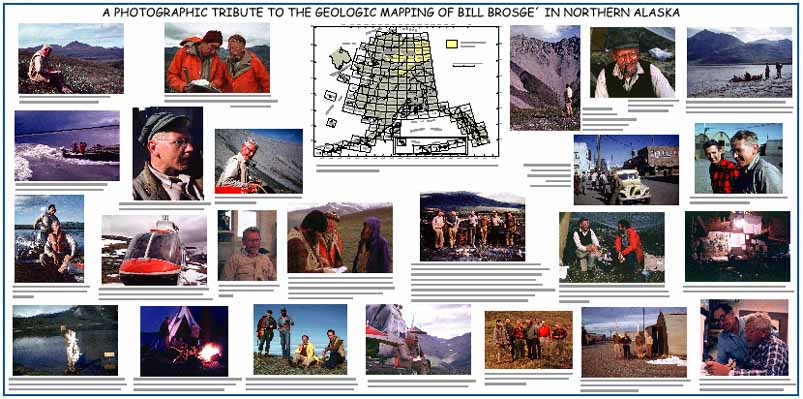

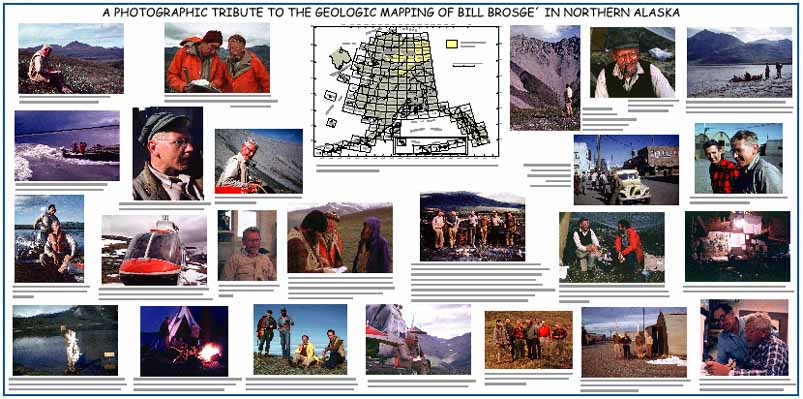

On April 7, 2001, William P. Brosgé, of the U.S. Geological Survey received the Dibblee Medal for his achievements in geologic mapping in Alaska. As Bill could not be present to receive the award, Tom Moore went to Los Angeles to accept it on Bill's behalf. The presentation was made at Placeritas Canyon Park in Newhall at the end of a premeeting field trip of the ongoing Cordilleran Section-Pacific Section SEPM meeting in Universal City. Tom brought a poster he composed that presents 23 images of Bill's work from 1950 to 1985. Below are the texts of Tom's tribute and Bill's acceptance remarks along with the photographs and a link to an Adobe Acrobat PDF file of the poster.

Map of Alaska showing locations of 1:250,000-scale quadrangles. Quadrangles mapped by Bill Brosgé are shown in yellow (If you click on the map, you will get an Adobe Acrobat PDF version of the map on which you can zoom and read quadrangle names and such).

A Tribute to William P. Brosgé Given on the Occasion of His Award of the Dibblee Medal, April 7, 2001

By Thomas E. Moore

Good afternoon. I'm pleased to be here today representing Bill Brosgé on his receipt of this award, an award he richly deserves. There are many people who could better represent Bill, especially his long-time colleagues in the Geological Survey, Hill Reiser, Tom Dutro, and George Gryc, but for various reasons each are unable to attend today's ceremony. I worked as a field assistant for Bill for about 4 years while a student, including three field seasons in Alaska, and Bill was one of my most important mentors along the way to a career in Alaskan geology. So it truly is a pleasure for me to be able to share some of my thoughts about Bill's contributions to Alaskan geology as well as read to you the remarks he sent along with me.

Bill was born in the Bronx in New York City and received his Bachelor's degree at Columbia University in 1942. At graduation, he heeded the nation's wartime call for geologists and joined the Survey in Washington D.C. where he made topographic maps from air photos of important areas for the military throughout the world. It was at the Survey that he met his wife, Mary, who he married in 1944. After the war, Bill returned to Columbia for graduate school, completing all the requirements for a Ph.D. degree except for a dissertation, while mapping in Virginia for the Survey. In 1949, he took advantage of the opportunity to go to the North Slope to map in the Naval Petroleum Reserve for Survey and the Navy. That summer, he mapped the Umiat-Maybe Creek area, where the Navy had made one of the first oil discoveries on the North Slope, and which remains a good oil prospect to this day. That work became Professional Paper 303H, still used as one of the classic studies of North Slope geology. The next year, Bill began mapping in the Brooks Range to the south, beginning the stratigraphic studies and geologic mapping that would occupy most of his career. The mapping in northern Alaska resulted in the publication of 34 geologic maps and a total of 100 geologic reports. Among his accomplishments, Bill defined and mapped Prudhoe Bay stratigraphic section in its classic exposures in the northeastern Brooks Range and was the coleader of the first appraisal of the oil and gas potential of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 1980. Bill worked in the Alaska Branch of the Survey for his entire career, first in Washington D.C. and, beginning in 1959, in Menlo Park. He officially retired from the Survey in 1984, but has worked as an emeritus scientist until just this past year, completing the maps of the Arctic and Christian quadrangles that are on display here today.

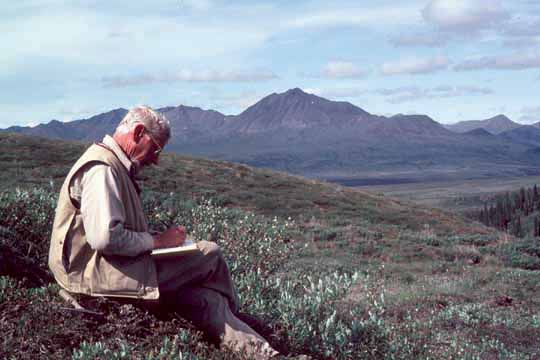

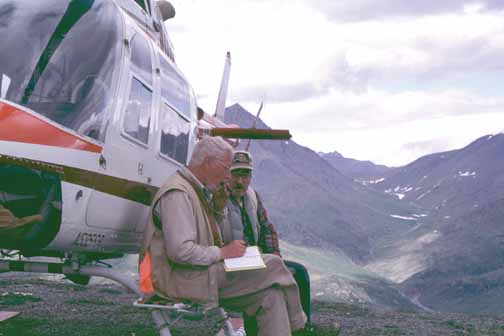

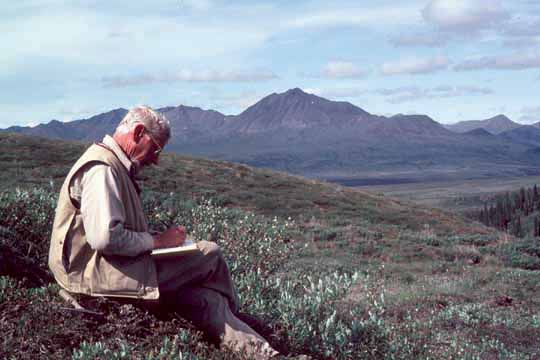

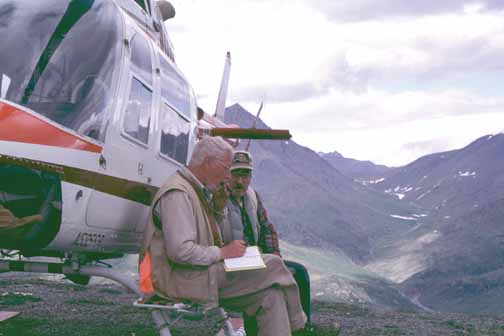

Bill taking notes at a station in the Wiseman quadrangle, 1981. Photo by T.E. Moore.

In addition to his achievements as a geologist, Bill was an explorer. In 1951, he was part of a geological field party that was only the fifth government expedition to make a land crossing of the central Brooks Range. Much of his early work was conducted by boat along rivers, by float plane from lakes, and by weasel, a jeep-like amphibious tracked vehicle that was designed for wartime landings in the South Pacific and imported into northern Alaska by the Navy. He worked in terrain that had not been explored, named or mapped. As Bill and his colleagues entered new territory, they were uncertain whether the rocks would prove to be Tertiary or Paleozoic-it was for them to discover. A typical field season began by placing food and gasoline caches at various points by ski plane along the summer's planned study area. In May, the field party would travel from Washington D.C. to the Fairbanks and then to the North Slope, waiting at a staging area until the snow melted in June to begin field work. Field seasons would be completed in early September. There were no maps at all in this part of Alaska until the late 1950's when planimetric stream-drainage maps became available. 1:250,000-scale topographic coverage did not become available until the 1960's, and inch-to-the-mile scale map coverage was not completed until the late 1980's, well after Bill's official retirement. For many years, Bill worked mainly by using oblique airphotos shot by the Navy as part of its petroleum exploration program in the Arctic in the 1940's, transferring this mapping to the 1:250,000-scale topographic base maps as they became available.

Bill was among the first to employ helicopters in geological mapping in Alaska. Unfortunately, the first attempt in 1950 ended in disaster with the drowning of one of his party members when the very underpowered helicopter crash-landed in a partly ice covered lake near their camp in the north-central Brooks Range. That lake was renamed Shainin Lake in honor of the geologist who died there. By the late 1950's, helicopter technology had been greatly improved and helicopters became the primary mode of transportation for geologic mapping in Alaska. The advantages of helicopters are obvious: large amounts of ground can be covered rapidly, access to advantageous viewpoints and outcrops can be easily and quickly obtained; and work over a wide area can be conducted from a single base camp. These machines have become essential for mapping the huge remote areas that characterize Alaska. The skills required to utilize helicopters for geologic mapping, however, are often not appreciated. Navigational skills in unmarked terrain must be excellent simply to arrive at the work area and to return home-one can easily lose their bearings, especially in areas of low or complex relief and in bad weather conditions. Similarly, a geologist must be extremely rapid and decisive at making his observations and interpretations of the geologic relations and accurate in his portrayal of them on a map. There is little time to meditate on or consider what one is seeing from the aircraft before it is out of view. Second and third passes at contacts can be made, but often leave the average geologist with his map spinning in his lap and uncertain of both his own location as well as that of the contact he is mapping and often no more certain of the geologic relations he is mapping. And, as every geologist knows, much of the most confusing geology is always at the join of maps--even more so where four maps join together-a particularly difficult problem to deal with under the time and space limitations of a helicopter. The average geologist can easily end up with his entire collection of maps in a heap on the floorboard of the helicopter-a situation that has happened to me more than once, I must confess! Bill, however, was the master of all of this. He helped invent the techniques, after all. I can't remember a time when he was uncertain of his location. His ability to spot and to quickly and accurately place a contact on the airphoto from the helicopter was uncanny. He used the helicopter for mapping like a cowboy uses his horse to lasso calfs at a rodeo.

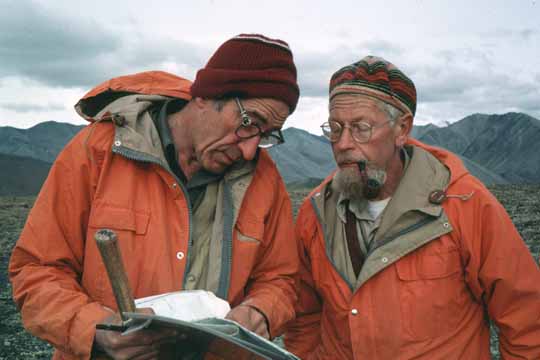

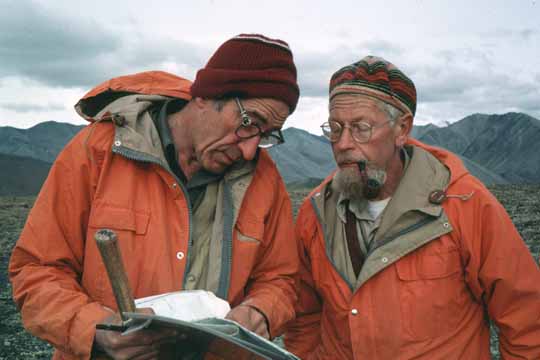

Long-time colleague Hill Reiser (left) and Bill Brosgé discussing map relations in the Arctic quadrangle, 1979. Photo by T.E. Moore.

During most of his career, Bill work with a core team of scientists that consisted of himself, paleontologist Tom Dutro, fellow geologist Hill Reiser, and a field assistant or two, such as myself. Bill was the unquestioned leader of this group in the field. He flew in the front seat, drew most of the lines, and each night made plans A, B, and C for the various weather possibilities that might be encountered the next day. Bill was never noted for how fast he could scale mountains, how long his traverses were, or how late he stayed up working on his maps each night. Instead, we left each day promptly at 8AM and returned about 5PM, day after day. It was his methodical, workmanlike steadiness employed over field season after field season and in the office that characterized Bill's work. Certainly, it is this character that resulted in the completion of so many map products for the Geological Survey. Nearly everyday that I make decisions as leader of field parties in Alaska, I draw from, and strive to match, Bill's example of steadiness, prudence, clear thinking, egalitarianism, and his decisive leadership of his field parties, as well as his earnest friendliness, humor, and unpretentiousness.

Bill clearly loved making maps of Alaska for the Geological Survey. Many of Bill's maps are simple reconnaissance maps published in black and white as open-file reports. Bill's excellence as a mapper is most clearly demonstrated by the shear amount of territory he covered. His ability to accurately and thoroughly assess the stratigraphy and depict the distribution of rock types in an uncharted land from an amazingly few helicopter landings and river traverses is unmatched. He didn't have time to ponder the structure and tectonics of the rocks he mapped. As a result, most of his maps are best termed lithologic distribution maps. For those who haven't worked in Alaska, it is difficult to visualize the vast area he covered. Here are some different ways to think of it: with his colleaques, he established the basic stratigraphic framework and mapped and published 13 1:250,000-scale quadrangles, the equivalent of 76,000 square miles, 13% of the total land area of Alaska! This is more than the equivalent of all of the area of California south of Fresno. His maps encompass the eastern two thirds of the Brooks Range, one of the great fold-thrust belt orogens in the world. The rocks in the Brooks Range are not simple geologically. The phyllites and schists Bill mapped in the internal zone of the orogen in the southern Brooks Range, in particular, will probably always be a mystery because of the difficulty in determining their stratigraphic age and the impact of the multiple deformational episodes that affected them. Bill's maps are valuable because he didn't put the geology into fashionable models that would become outdated as geologic concepts and knowledge changed. Instead, he just mapped them as he saw them. As he mapped, Bill imagined that his crew was the vanguard of legions of geologists who would more thoroughly study the structure and stratigraphy at a later date. Accordingly, he made reconnaissance maps, believing they would be greatly improved by others within a few years. That was more than 20 years ago for most of his maps. While there have been some improvements in a few areas he mapped, most of Bill's maps have remained completely unimproved since he was there. And, with the present levels of support for geologic mapping in Alaska and the increasingly difficult problems accessing these remote areas, his maps are likely to remain the only resource for a huge region for a couple more decades at least. It's very fortunate that Bill's maps are characterized by accuracy and honesty. Although they may often be reinterpreted by others, the northeastern part of every geologic map of Alaska now and for a long time into the future will display the stratigraphy he defined and the lines he mapped.

I am in complete awe of all that Bill accomplished and respect his work tremendously. And I'm very pleased that the Dibblee Foundation has decided to honor Bill with this award.

Bill viewing the sub-Mississippian unconformity, Demarcation Point quadrangle, 1969. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Remarks of William P. Brosgé on Receipt of the 2001 Dibblee Medal for Geologic Mapping, April 7, 2001

Thank you for this Award. It is a great honor, and I am sorry I can't be here to accept it. But that's okay because the Award is not just for me. It is also for the work of all the other geologists with whom I was in the field for 35 years. I never worked alone; I was always part of a team. Sometimes the team was just Hill Reiser and me, but it usually included Tom Dutro and there were many other geologists from the USGS and the Alaska State Survey. That is why our last map has five authors.

There was a good reason for working as part of a group. A field season in Northern Alaska required organizing an expedition. Until 1975 there were no roads and only a few airstrips. Even working by boat required that caches of food and gasoline be set out in advance. The Alaskan Branch realized this from its very beginning. If it is so hard to get into the field, you better do all the work you can once you get there. We did pretty well. In one generation, about a dozen Alaskan geologists, both Federal and State, plus countless field assistants and future geologists and including three geologists who were killed on the job, turned an almost blank geologic map of northern Alaska into a pretty good reconnaissance map of an area almost one half the size of California. Now we know where the problems are, and the next shift is working on the details.

Bill at spike camp on the Hulahula River, 1970. Photo by Hill Reiser.

I especially want to thank Tom Moore for accepting this Award on my behalf. All my older contemporary colleagues are kept home by ailments, so it is good that there is a next generation. There may even be a chance for a newer generation to do more work now that there is renewed interest in the North Slope.

All of this sounds pretty grim and serious. Actually it was a lot of fun-like being a perpetual Boy Scout and getting paid for it with free float plane trips and helicopter rides thrown in.

And my thanks to Tom Dibblee. I remember the last time I saw Tom right after he retired. My wife and I stopped in to see the Dibblees on our way home from Santa Barbara and, after showing us around the ranch, Tom asked whether I could drive his old Survey truck back to Menlo Park. "Sure", I said,"if my wife drives our car and I can drive the truck". After awhile, Tom said, kind of slowly: "It hasn't boiled over for the last 25 miles". Well, it was a suspenseful trip, but we just kept rolling along. I wish the same for Tom. So, my best to Tom, and thanks to you all.

Field work by boat on Galbraith Lake, 1950. Galbraith Lake lies along the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and Dalton Highway which were built about 20 years after this photo was taken. Photo by Hill Reiser.

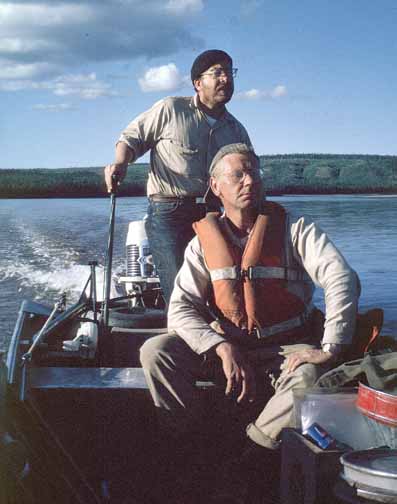

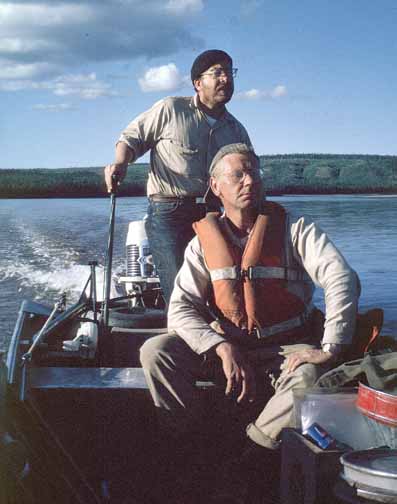

Bill at the tiller on field expedition along the Porcupine River, 1964. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Bill waiting for an airplane during camp move, Echooka River, 1950. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Mapping the Philip Smith quadrangle, 1976. Photo by Hill Reiser.

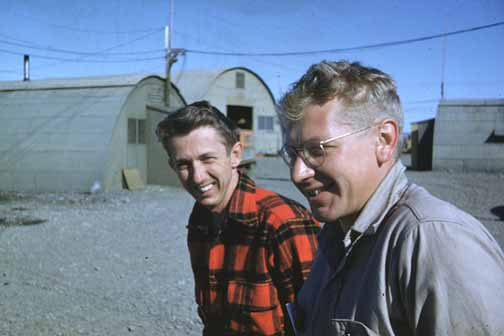

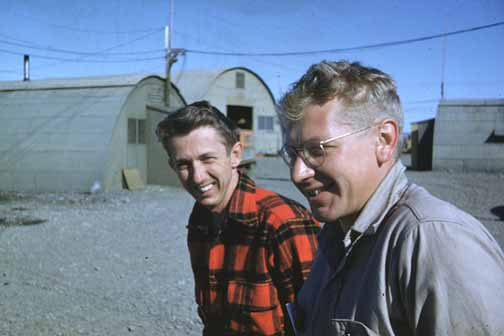

Bill on Cushman Street in Fairbanks during preparation for 1950 field season. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Bill (right) with unknown field assistant in Umiat, 1950. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Tom Dutro (standing) and Bill crossing the Porcupine River, 1964. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Bill taking notes in a warm helicopter bubble on a cold day in the Wiseman quadrangle in 1981. Helicopter pilot Cy Asta reading book at left. Photo by T.E. Moore.

Bill in the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory (NARL) cabin at Lake Peters, 1969. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Bill discussing the day's field plans in the Wiseman quadrangle, with John Dillon (left) and Dave Adams (right) of the Alaska Division Geological and Geophysical Surveys. Dillon died in a plane crash in the Brooks Range in 1987. Photo by T.E. Moore.

Expedition that traversed the Brooks Range in 1951. From left to right: Bill, Gordon Herreid, Jack Warne, Dick Olsen, Red Grady, Marv Mangus, and Bill Patton. The party climbed Brooks Range from north using Weasels (the tracked vehicles in background) and descended southward on the John River by boat. This party was only the 5th government expedition to cross the central Brooks Range. Photo taken on upper John River (Wiseman quadrangle) after completion of the Weasel segment. Photo by George Gryc.

Bill and Tom Dutro in spike camp in the Demarcation Point quadrangle, 1970. They subsisted on, as well as sat on, C-rations for the duration of the camp. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Bill doing evening map compilation at Crevice Creek Ranch, Wiseman quadrangle, 1981. Photo by T.E. Moore.

Bill celebrating the end of a long field season at Takahula Lake, Survey Pass quadrangle in 1962. Sign says "Harry's Pier-- Fish, Buffalo Chips Served" Photo by Hill Reiser.

Camping on the Sheenjek River during the late summer, 1952. Left to right, Dick Olson, Marv Mangus, Bill Brosgé, Tom Dutro. Photo by Hill Reiser.

A meeting at the international boundary in 1980. Left to right: Don Norris (Geological Survey of Canada), Cy Asta (pilot), Bill, and Hill Reiser. Photo by Tom Dutro.

Bill with Tom Dutro discussing the stratigraphy of the Wiseman quadrangle in 1981. Photo by T.E. Moore.

Bill and field crew at Nigu Lake at the end of the 1950 field season. From left to right: Steve Dwornik, Hill Reiser, Bill, John Downs, Bill Nystrom, Bernie Armbruster, Clair Gudim. Hill Reiser photo.

USGS geologists at Umiat, 1951. From left to right: Bill Patton, Marv Mangus, Gordon Herreid, and Bill Brosgé. Photo by Hill Reiser.

Hill Reiser (left) and Bill reviewing the rocks captured in the Brooks Range and brought back to the office, 1985. Photo by E.R. White.

Presentation of the Dibblee Medal

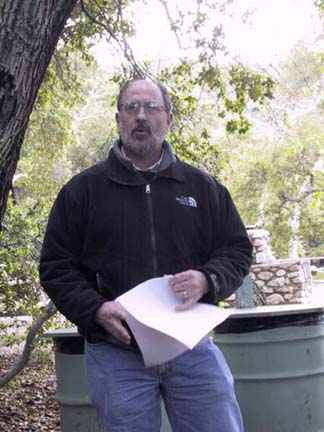

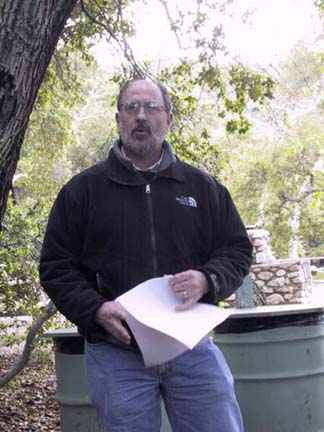

Tom Moore making his tribute to Bill Brosgé. Photo by Peter Wygand of Cal State Northridge, a leader of the field trip on which Bill was awarded the Dibblee Medal.

Tom Dibblee (right) presenting the Dibblee Medal which was received for Bill Brosgé by Tom Moore (left). Photo by Peter Wygand.

Tom's Poster in Acrobat PDF format

CLICK HERE to view the poster Tom Moore took to the award presentation. This file is 47" x 24" in PDF form that uses the Adobe Reader plugin on your browser (poster.pdf, 7.5 MB; large but print quality). To view it, you will need Adobe Reader 4.0 or higher. You can download a copy of the latest version by clicking the button above.

Text by Bill Brosgé and Tom Moore. Photos by Hill Reiser, Tom Moore, George Gryc, Tom Dutro, and E.R. White. Web page by Mike Diggles.

Send e-mail about this report to

Tom Moore (tmoore@usgs.gov).

The URL of this page is http://www.diggles.com/wbrosge/index.html

Date created: 04/09/2001

Last modified: 2/8/2006

Send e-mail about this Web site to

Mike Diggles (mdiggles@usgs.gov).